I never called it a “trauma.”

The word felt reserved for catastrophes far beyond what I endured, and I never wanted to appear overly dramatic. Yet, more than a decade later, I still carry the emotional and mental weight of my son’s birth—a birth that, in hindsight, was one of the most profoundly traumatic experiences of my life.

After years of battling cancer and facing infertility, my husband and I were overjoyed to learn we were expecting our first child in June 2008. My pregnancy, while mostly uncomplicated, was incredibly uncomfortable, and by the time I went into labor, I was beyond ready.

I labored through the night and into the following day. Hours of pushing led to a vaginal delivery of our 8lb 13oz son, aided by a vacuum after an episiotomy failed to prevent a third-degree tear. I pleaded for help throughout, but nothing could have prepared me for what came next.

When my son arrived, he was limp and blue. The umbilical cord was wrapped around his neck and he had been exposed to meconium. The nurses whisked him away immediately. Several moments passed before we heard his first weak cries from across the room. I was exhausted, overwhelmed, and terrified—and it only got worse.

As the doctor stitched up my episiotomy and tear, I kept my eyes closed, focusing on breathing. But then I heard it: the sound of liquid spilling, in repeated gushes. I knew something was wrong. My husband, across the room with our son, saw the blood pooling on the floor and understood too.

Twenty minutes went by. I had not delivered the placenta. The doctor’s hands moved inside me with urgency, and I heard the orders shouted in rapid succession: “We need an OR room now! Have two units of blood ready! Page Doctor!” The fear in their voices was unmistakable.

I couldn’t open my eyes. I called to my husband and heard him say, weakly but tenderly, “I love you,” as I was rushed to the operating room. He stayed behind, sitting on the floor of our hospital room, just feet from the blood I had lost, while nurses cared for our son.

In the OR, the doctor explained the situation: I was hemorrhaging severely, my life was at risk, and I might need a hysterectomy. My only response: “Do what you need to do.”

Six hours after my son was born, I woke in the ICU, still intubated and connected to machines I couldn’t begin to identify. The first thing I asked my mother was, “Did I have to have a hysterectomy?” Tears welled in her eyes as she nodded: “Yes.”

The doctors had tried everything else. Without surgery, my survival chance had been estimated at 10%. After eight units of whole blood, two units of platelets, two units of plasma, and relentless efforts to stop the bleeding, an emergency hysterectomy saved my life.

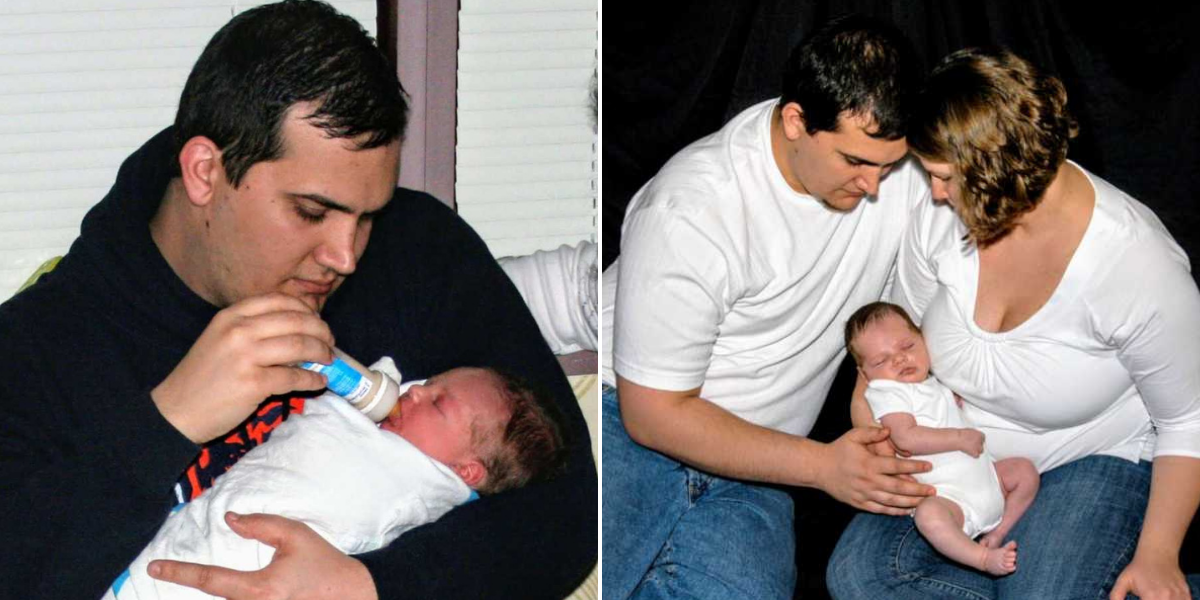

I woke again, another six hours later, still in the ICU, disoriented by time. My body was swollen from head to toe from all the fluids pumped in to stabilize me. Stretch marks traced new paths across my arms, my face so puffy that my eyelids turned inside out. My son was now 12 hours old, and I had yet to hold him. My husband showed me his picture on our camera screen. I kept asking when I could finally be with him.

Eventually, I was moved to a regular postpartum room, though I wasn’t ready. I couldn’t move freely, couldn’t control my bodily functions, and felt painfully exposed. The staff went about their routines, treating me like a typical postpartum patient, which only deepened my sense of isolation and frustration.

After a few more nights, we finally went home—but the ordeal wasn’t over. My episiotomy and tear became infected, likely due to swelling and stitches pulling apart. I couldn’t lift anything or even move easily. Climbing the stairs became a crawl. Simple trips to the bathroom were a challenge. I needed help for everything, yet desperately wanted independence.

Breastfeeding, too, became another source of stress. My son had started on formula immediately, and the pain medications and antibiotics I required meant I had to pump and discard milk if I wanted to preserve any chance of feeding later. The effort added unnecessary pressure and frustration, and eventually, our attempts to breastfeed were minimal at best.

Weeks of pain, lingering infection, chills, aches, and weakness followed. My husband returned to work after a few days, leaving me reliant on family and friends, which only heightened my sense of inadequacy. I juggled postpartum care, newborn appointments, and delayed cancer follow-ups, all while grieving the loss of my fertility. The family we had dreamed of building suddenly felt painfully out of reach.

I recorded in my journal that the doctor had commented on my emotional state, noting that many women struggle with depression even after uncomplicated deliveries. In my case, the near-death experience and hysterectomy made emotional turmoil inevitable. He referred me for support—but at the time, it felt like too much, one more burden I couldn’t carry.

Looking back, I know I never fully recovered. The mental and emotional scars from that day run deeper than the physical scar etched across my pelvis. Now, I am finally in therapy, slowly working through the trauma.

If there’s one piece of advice I could offer to another woman who experiences a traumatic birth, it would be this: it is okay—necessary, even—to acknowledge that you have been traumatized. You don’t need to push through alone for years or decades. Seek help—physically, mentally, and emotionally—when you need it. There is no reason to carry it all silently.