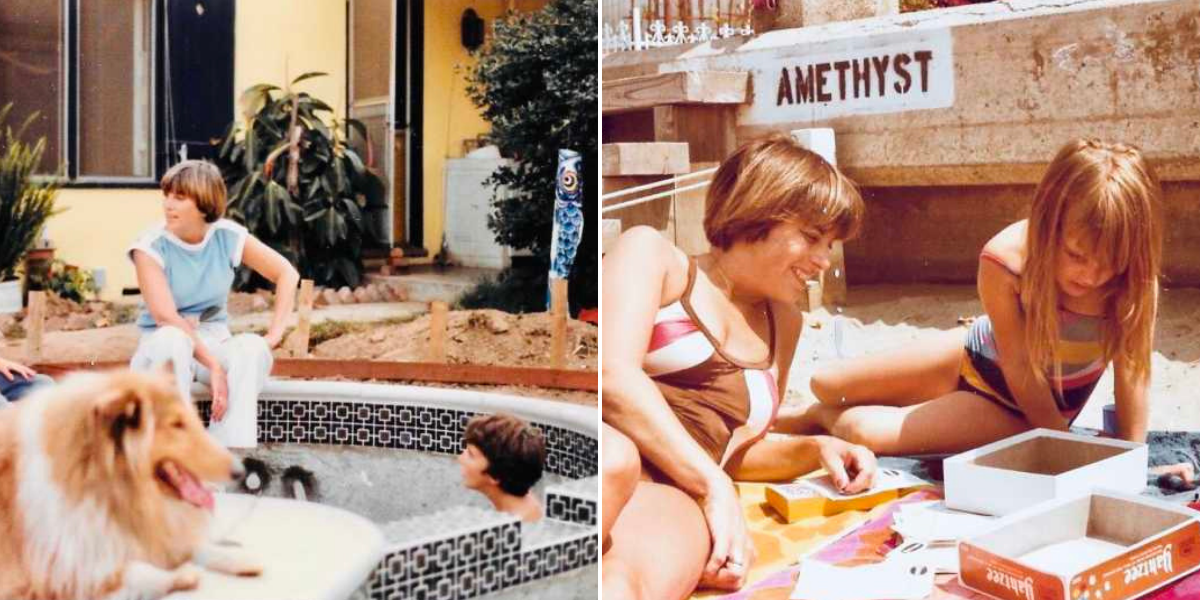

I rarely, if ever, got sick as a kid—not for lack of trying. I knew that being sick meant I didn’t have to go to school, a philosophy I’m pretty sure my mom planted early, sometime around age four, after she and her friends hosted a classic “chicken pox party.” You know the kind: one kid got the dreaded disease, and all the other moms brought their children over, hoping they’d catch it and be done with it. I imagine the adults sat around drinking wine while we kids played “Ring Around the Rosie” or any game that required hand-holding. With my mom and her friends, it was probably Twister—but you get the idea.

I became something of an expert at faking illness. Once, inspired by my inner Ferris Bueller, I held a mercury thermometer up to a lamp for far too long. I don’t know how long exactly, but my mom definitely caught on when my temperature read 112 and I was very much alive. I tried so many times to fake being sick that when I woke up one morning with a searing pain in my eye, my mom muttered, “There better be something in your eye,” more than once on the drive to the ophthalmologist. As it turns out, there really was—a metal sliver lodged in my eye, which the doctor pulled out like a splinter from a long day on the playground. The strange part? It somehow appeared while I was asleep. I never did solve that mystery, but in hindsight, it felt like a preview of how my life would unfold.

Thankfully, I didn’t break a bone until adulthood—by then, I had a gaggle of kids and tripped over a cat one of them brought home and insisted should live with us. Maybe it was underfoot, or maybe it was slippery from the sunscreen my daughter thoughtfully rubbed all over it. After all, we wouldn’t want the cat to get sunburned. I did, however, split my chin open once as a child during a heated competition with my brother to see who could sharpen a pencil faster. Apparently, he won. I tripped running to the wall-mounted pencil sharpener and went face-first into the floor. My babysitter decided a few butterfly bandages would do—even though bone was visible. My doctor disagreed. After six stitches, I was back to bouncing off the walls like nothing had happened.

That is, until the day the itching started. Then came the fever. Then the angry red rash that covered my eight-year-old body. Even my mom couldn’t deny something was wrong. She rushed my calamine-soaked self to the doctor, who promptly announced I had Scarlet Fever. My eyes widened, my heart raced, and my entire life flashed before me. The only place I’d ever heard of Scarlet Fever was on Little House on the Prairie, and on that show, people either died or went blind. I wasn’t sure which was worse. Would I never see John Travolta dance in Grease again? Would I have to attend the same blind school as Mary Ingalls? Would I ever see the sparkling blue eyes of my childhood crush again as he nailed me with a dodgeball? I had no idea what to think or how to fight such a terrible plague—so I did the only thing I could. I cried.

I was certain death was imminent when my mom brought me home, laid me on crisp white sheets, and offered to make my favorite sick-day meal: peanut butter and lettuce on white bread. I have no idea how that combination became a thing, but it was the cure-all of my childhood—just not this time. No amount of oatmeal baths, soothing songs, or questionable sandwiches could save me. I was convinced I was going to die. All I could think about was how I wished my hair were longer so my curls could spill over my shoulders in the coffin as townsfolk came to pay their respects, covering their mouths with handkerchiefs like Mrs. Olson so they wouldn’t catch the disease. I even composed my epitaph: Here lies a girl, taken too fast. She should’ve gone to school and studied in class. In a moment of pure desperation, I promised God that if He let me live, I’d never fake sick again—and I’d finally learn how to find the circumference of a circle.

By the time my mom returned with my sandwich, I was drowning in tears. She climbed into bed beside me, wrapped her arms around me, and rocked me as I wailed. I dramatically threw the back of my hand to my forehead and cried, “Go! Save yourself!” insisting I couldn’t risk giving her the plague. She laughed—deep, belly laughter. I stared at her, completely unamused, unable to see the humor in my impending death. Though, to be fair, I did always suspect she liked my brother better.

Once she caught her breath, she pulled me closer and explained. She told me I wasn’t wrong—people once did die from Scarlet Fever. Then she explained antibiotics, reassured me I would be fine, and promised I wouldn’t miss a single episode of The Dukes of Hazzard.

If I haven’t mentioned it before, my mom was a teacher—and an incredible storyteller. I think that’s where my love of writing comes from, even though she never wrote herself. She had a way of explaining things, of turning everything into a teachable moment. She taught us how to spot poison ivy, how to find the Big Dipper, and how to wonder what Native Americans thought when they first looked out over endless plains. She made boring facts interesting, created skits to help me memorize speeches, and stood off to the side acting them out so I wouldn’t forget what came next. She had a gift for making everything make sense.

So that day, as I wiped away my tears, it wasn’t just the peanut butter and lettuce sandwich that calmed me. And it wasn’t only the pill that healed me. No—it was my mom. It was always my mom.

PS: I never did figure out how to find the circumference of a circle—but I promise I tried. I really did. Well… at least on the days I actually showed up for math class.