When my son was around eight months old, our family began noticing something unusual—his eyes made a clicking movement whenever we rocked him. At first, I hadn’t really paid much attention, but I decided to mention it to his pediatrician. Around the same time, he had also started occasionally bobbing his head up and down. I didn’t feel alarmed, but I sent a quick text to our pediatrician just to be safe. His reply came back: “This looks like nystagmus, a shifting of the eyes. Have you noticed anything else unusual?”

I hesitated, then admitted, “Well, now that you mention it, he’s not sitting up or rolling over as much as I expected.” I had grown used to later development thanks to my older son, so I didn’t think much of it. My firstborn had crawled at 14 months and walked at 20 months, while this little one wasn’t sitting unassisted by eight months. Despite that, our doctor recommended a referral to a neurologist to investigate further. I remember feeling a heavy weight of worry—I didn’t know what the future held. And of course, Google was no help.

This was the beginning of a long journey toward a diagnosis. We made appointments with a neurologist for bloodwork, scheduled an EEG, an MRI, and additional tests, and also saw an eye doctor. Every step was a waiting game, a mix of hope and anxiety. Thankfully, we leaned on each other, supporting one another through the uncertainty. After countless tests and appointments, in October 2016, we finally received a name for what our sweet boy was facing: Congenital Disorder of Glycosylation.

I remember the moment the doctor shared the diagnosis. I immediately felt a rush of fear and disbelief. “We think Jackson has Congenital Disorder of Glycosylation,” she said. My mind spun. “Wait—what? He has what? Will he walk? Will he talk?” The questions tumbled out as emotions took over. The doctor admitted that it was so rare she didn’t know exactly what to tell me. She explained, “The more severe cases may pass away by the age of one,” and handed me a few websites to learn more.

I felt shattered. “Pass away? Not my child,” I thought, devastated at the life I had imagined for him slipping away in an instant. From that moment, I immersed myself in research. I read everything I could find, connected with families who had children with disabilities or rare diagnoses, and slowly found comfort in knowing we weren’t alone. My family and friends were my anchors—they were there when I cried, when I screamed, and when I simply needed someone to listen.

Since then, we’ve worked with genetic specialists, undergone more bloodwork, and completed extensive genetic testing in search of the gene responsible for Jackson’s condition. Sadly, the gene has never been identified, so technically, our sweet boy remains undiagnosed. We don’t know why his body functions differently, but we’ve learned to navigate life as it comes.

I mourned the little boy I had imagined, the life I thought we’d have. I had been so excited to raise my boys just 17 months apart, to watch them grow together, play sports, and become lifelong friends. That vision changed the day of the diagnosis. I allowed myself to grieve, hoping that even if life looked different, my boys would still share love and connection. Once I accepted that reality, the blessings began to flow in ways I hadn’t anticipated.

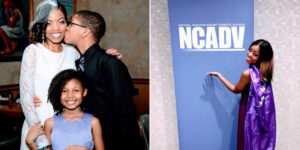

Lincoln has been an amazing big brother. He shows incredible kindness toward Jackson, though they still have all the typical sibling squabbles. Jackson sat unassisted and began army crawling at 2.5 years old. Now, at three and a half, he is crawling on his hands and knees and walking with assistance. We give him all the support he needs, and while we don’t know exactly what his development will look like, we hold onto hope. So far, he’s simply following his own timeline, and that gives us hope—always hope.

The hardest moments, surprisingly, aren’t the physical challenges—they’re when people feel sorry for me. I want to say, “There’s no need to be sorry. We love our son, and we couldn’t be more grateful for him.” It’s hardest when Jackson wants to play with his siblings but can’t, or when he is left out because environments aren’t designed for inclusion. Some parks, for instance, offer nothing accessible for him. It’s not the wheelchair that’s the challenge—it’s the lack of inclusive spaces. We need to create more of them for all children with disabilities.

My advice to anyone receiving a diagnosis is this: allow yourself to mourn the child you thought you had, the life you imagined, and then move forward. There is immense strength in accepting this new path. Your child is still yours, still incredible, and capable of amazing things if you let them shine. You will learn, grow, and advocate in ways you never expected. You will meet people you wouldn’t have met otherwise. Welcome to this new life—it may not be the one you imagined, but different is not less. It’s just different, and different can be beautiful.