Purple has always been my mom’s favorite color. Since it was the 1970s, it must have been easy to find a purple dining table with matching purple leopard-print roller chairs to celebrate that love. The kitchen, dining area, and even the bathroom were wrapped in varying shades of lavender, from the walls to the linoleum floors. Growing up, it was a fun, quirky hallmark of our home. Beyond her love of purple, my mom was also a devoted, caring mother to her three children.

That sense of amusement ended when I was thirteen, on a day I will never forget—the day purple and I became enemies. I walked in the door expecting supper and instead stepped into the beginning of years of heartache, confusion, and anger directed at an invisible illness. My normally quiet, reserved mother sat on her purple chair beside the purple table, babbling nonsensically about her purple ten-dollar bill. There was talk of a magician and other delusional thoughts that made no sense to me. That night marked the first of many hospitalizations. Each time, she would disappear from our family life for at least a month. It was also when I learned her bipolar illness wasn’t new—it had simply lain dormant for years. Before I was born, she had already experienced episodes. At the time, it was called manic depression, later renamed bipolar mental illness.

During that episode, my dad asked if I wanted to stay with a friend. I refused. Instead, I became fiercely independent and guarded, rarely sharing what was happening at home. I rejected sympathy from friends or family who knew, recoiling at how closely it felt tied to pity.

Over time, purple became my unconscious symbol of the destruction of our mother-daughter relationship. My mom’s bipolar illness resurfaced regularly—sometimes once a year, sometimes twice. The signs became familiar: sleepless nights, nonstop talking on the phone in the early morning hours, impulsive shopping sprees with bags of unnecessary items. Then came the silence, the cleanup, and another hospitalization. Each time she returned home, she expected to resume her role as a parent. Each time, I resisted. It was a painful, heartbreaking period for us both.

My grandmother—my mom’s mom—was also bipolar, and I wondered if my fate was already sealed. My dad reassured me I was different and told me this adversity would make me stronger. As I grew older, I began to believe him. Still, the loss of a close, bonded mother-daughter relationship felt like an enormous price to pay. At times, trading my inner strength for that closeness was tempting, especially when I saw other women cherish the special relationships they had with their mothers.

At eighteen, just one month after my dad passed away, it became my responsibility to hospitalize my mother. Losing my father so young was devastating, but my mom’s pain ran even deeper, and her illness could no longer be contained. I don’t remember the warning signs this time. Somehow, I managed to get her into the car and to the emergency room that afternoon. My dad had always shielded us—when symptoms appeared, he took her to the hospital, and that was all I knew. This time, the weight fell on me. We were placed in a small room. She flicked the light switch on and off repeatedly, tried to leave, and I had to convince her to wait. Hours seemed to pass before the doctor arrived. They took my crying, angry mother away, and I went home completely stunned.

Visiting her over the next month was a shock—walking in my father’s footsteps, finally understanding how he must have felt. I can still picture her hand scraping against the window of her locked room, kept that way for her own safety. There were days she sat catatonic in a wheelchair, staring into space. As she improved, the behavior shifted to overly enthusiastic introductions to every patient on the ward. As painful as it all was, there was never a moment when I considered not visiting her.

Fast forward through years of repeated episodes, regular hospitalizations, and nearly two decades of living this cycle.

I still hated purple. I would never tell my mom, but it continued to represent the deep divide her illness had carved into our relationship. In 2008, my beautiful daughter was born. My husband and I were thrilled to give our son a sibling. When she turned two and declared pink as her favorite color, I felt relieved. Yet her presence forced me to confront old wounds I had carefully tucked away. I’m grateful for that, because they needed healing—including my hatred of purple. In those early years, I never bought purple clothes for her, though she was gifted many. I refused to pass my pain onto my innocent child, so she wore them. Slowly, it became impossible to hate a color wrapped around someone I loved so deeply.

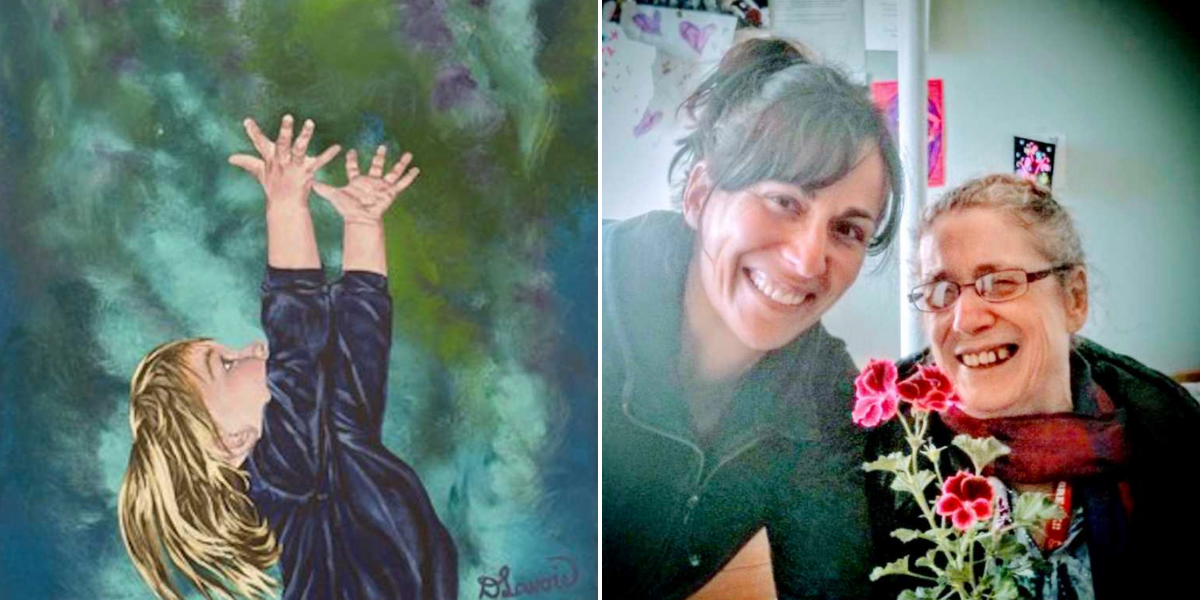

When I began my childhood painting series, one piece—Catch and Release—became a turning point. I chose to paint the balloon purple. The little girl in the painting plays catch with it, and the decision wasn’t accidental. I felt drawn to it, though I didn’t fully understand why at the time.

Like dreams, artwork can reveal meanings long after it’s created. Months later, I realized the truth hidden in that painting. I am the little girl. The purple balloon is my mom during moments when her illness is managed—when we can connect, let the sadness fall away, and simply be present together. When she becomes ill again, I must release her and stop trying to be her parent. I know she is safe, supported by caregivers and medication until she reaches the healthy side of the episode. The balloon is large—larger than the child—yet nearly weightless. It represents my inner strength. Even when situations feel overwhelming, I trust my ability to carry them. The phrase “purple power” comes to mind.

One cold January afternoon, after writing this, I walked to pick up my daughter from school. I glanced down at my maroon winter coat and smiled, realizing how far I’d come. After all, maroon is purple mixed with red—a color of love.

Purple will never be just another color.

But I’m glad we are friends.