I’m not going to beat around the bush—my life has never been easy. As a child, I faced circumstances completely beyond my control, situations that made it incredibly difficult to process the trauma unfolding around me. I learned early on how to hide what was happening inside my mind. I was terrified of being labeled “crazy” or “weird,” so I became the kid who smiled too much, laughed too loudly, and acted overly happy, all while being far too afraid to ask for help.

From the outside, my life appeared perfect. But beneath the surface, I was battling inner demons from a very young age, quietly carrying pain no one else could see.

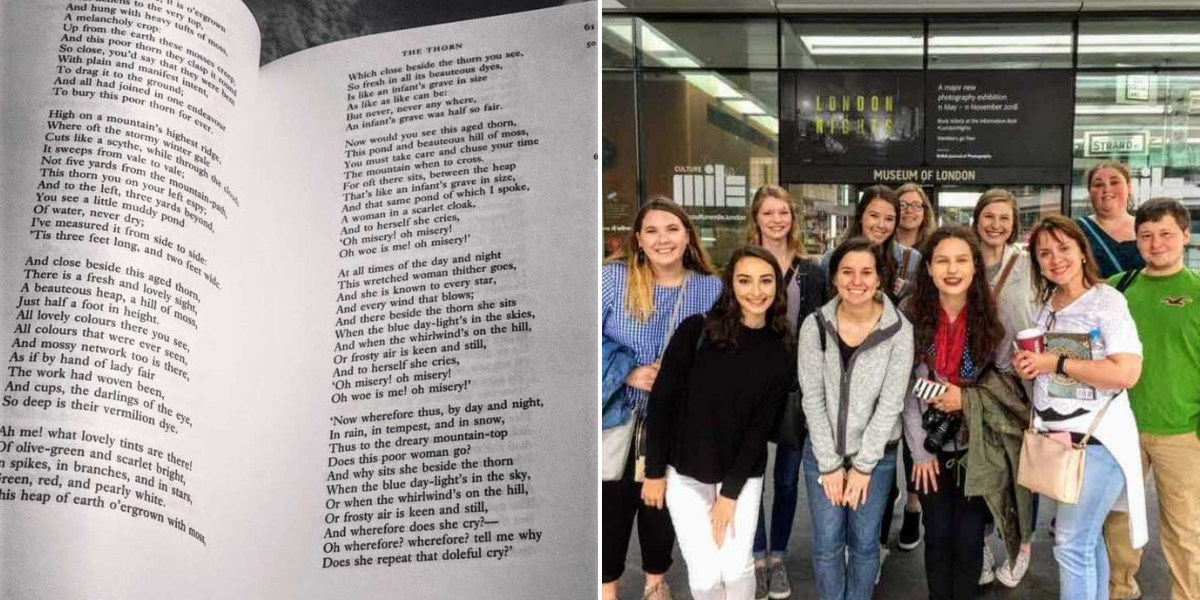

Those demons eventually took a devastating form. Before my 22nd birthday, I had attempted suicide four times. I had no healthy coping mechanisms, so I turned my pain inward, hurting myself in order to feel some sense of control or release. The only true escape I found was through literature. I lost myself in the works of poets like Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth. Their words transported me—onto a ship with an ancient mariner or into endless fields of golden daffodils. In those moments, the noise in my head softened. Poetry gave me hope when everything else felt unbearably bleak.

Because my life seemed so “normal,” July 22, 2018 began like any other day. When I woke up that morning, I never imagined I would attempt suicide later that afternoon. Just before deciding to go through with it, I was sitting in a Starbucks when an older woman struck up a conversation with me about the semicolon tattoo on my ankle. She had recently moved to my small Louisiana town from Michigan, and her daughter was struggling with her own mental health battles. I now lovingly refer to her as the “angel in Starbucks,” because in that brief conversation, she offered me a glimmer of hope in the middle of overwhelming darkness. Even though I still went through with the attempt, that moment remains proof to me that goodness exists in the world.

After my attempt, my aunt found me sitting in my car. I had intentionally triggered a severe allergic reaction, and she immediately called the police. I was absolutely terrified. The officers arrived, I was taken to the local hospital, and I was changed into a suicide gown. That night, I felt more alone than I ever had in my life. My thoughts raced—about my study abroad class and its upcoming paper, my responsibilities as an orientation leader, and the crushing belief that I had failed everyone who cared about me. I was convinced my support system would abandon me once they knew the truth. I wondered if anyone could still love me, or if my suicide attempt would now define who I was forever.

I spent a week in a mental hospital following that attempt. What stands out most in my memory are the sterile walls and the paper-thin scrubs. The hospital felt like controlled chaos, yet somehow, even there, I found moments of light. It wasn’t a pleasant experience, but it taught me something vital: I wasn’t alone. Others around me carried stories eerily similar to my own, and amid the chaos, there was a strange sense of safety and belonging.

When I was discharged, I expected relief—but instead, I felt more alone than ever. I had no idea how to tell people what had happened, who deserved to know, or who would stay. I was especially terrified to meet with the professor of my summer class. When we finally sat down together, I had been out of the mental hospital for only a few hours, and my hospital bracelet was still on my wrist. She gently helped me cut it off, and in that moment, it felt like I was severing my last connection to the one place that had recently felt safe. Suddenly, I was on my own again, and being alone terrified me. I clung to familiar people and places, desperately searching for stability.

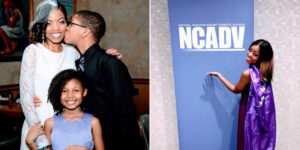

In the weeks that followed, I met with many people, but the most meaningful meeting was with my thesis advisor. When she saw me, she immediately hugged me and said, “I am so glad you are here to give a hug to.” I had expected disappointment or anger for not reaching out before my attempt. Instead, she simply wanted to support me. Through tears, I shared what my time in the mental hospital had been like, and she listened without judgment. In my most vulnerable moment, she became my saving grace. To this day, she remains my “mom-tor,” the woman I admire most, and I am endlessly grateful for her presence in my life.

After my attempt, I learned the true meaning of chosen family. While my biological family struggled to support me in the ways I needed, my chosen family stepped in without hesitation. They offered hugs, encouragement, and even laughter during my darkest moments. Their love came without obligation, and I am deeply spoiled by the amount of care they pour into my life when things get hard.

Even now, as I continue to battle mental illness daily, they remain my sunshine in an often overcast world. I realized I had surrounded myself with surrogate aunts, uncles, and sisters to walk through life with. I may not have fully understood love before college, but I understand it now—and there’s no turning back.

A few months later, I gained clarity when I was diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). For the first time, my experiences began to make sense. I learned how to recognize when my life feels out of control and how to use coping mechanisms to ground myself. Having BPD does not make me a monster, but it does help explain my repeated suicide attempts. While those attempts were deeply traumatic, learning more about my diagnosis has helped me understand how BPD fits into my life and how I can move forward.

As a society, we need to confront the stigma surrounding mental illness. People often grow uncomfortable when I share that I am a suicide attempt survivor. The greatest barrier to progress is ourselves. If we can acknowledge stigma, we can create space for honest conversations and better support for those who are suffering.

I also want people to know that attempting suicide does not make someone selfish. I was so desperate to escape my pain that I lost sight of who I was living for—myself or anyone else. Many survivors echo the same sentiment: they simply wanted the pain to end. That was true for me. I thought about the people I might leave behind, but I was overwhelmed by the desire to feel nothing at all. I was willing to go to any extreme just to make the pain stop.

One of the ways I’ve begun to heal is by helping others. During my senior year of undergrad, I organized a mental health event at my university. For the first time, I spoke openly about my struggles. From that moment on, I made it my mission to share my story and support as many people as possible.

My life could have ended after my suicide attempts, but I believe I survived because the world needs my voice. To help other survivors reclaim theirs, I developed an acronym called SALT—Stop, Act, Listen, and Talk. First, stop and recognize that the situation isn’t about you. Then act by finding ways to help. Listen deeply to the person confiding in you. Finally, talk to them—not about them—understanding that their life has been permanently altered. I hope SALT continues to grow and reach more people in the years ahead.

Every day, I remind myself that I am “here, alive, and breathing,” and that is enough. After my attempt, I never imagined I’d be able to look forward to the future—but now, I do. Life can feel overwhelming, and optimism doesn’t come easily, but I hope my story encourages others to keep going. Even when the darkness feels all-consuming, it’s the smallest glimmer of light that gives us the strength to persist.